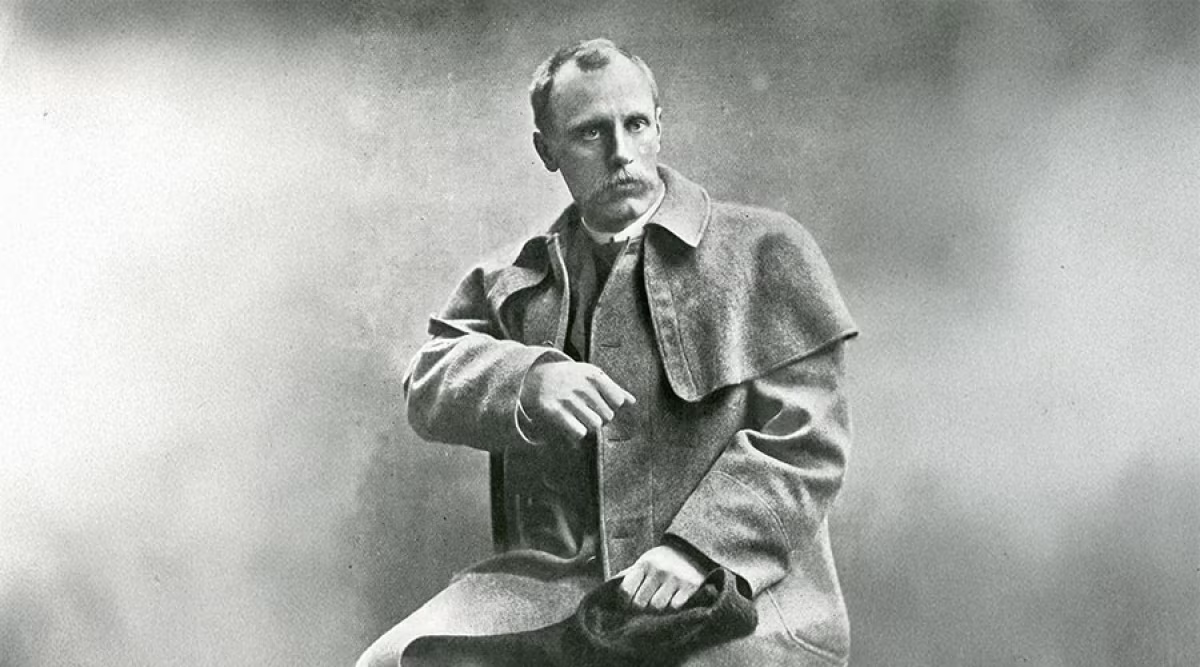

A seminal figure in Arctic exploration, Fridtjof Nansen was more than just an explorer; he was a scientist, humanitarian, statesman, and visionary whose daring expeditions into the Arctic helped reshape the world's understanding of the polar regions. Two remarkable Arctic expeditions defined his polar career, thrusting him into the spotlight in Norway and hailing him as a national hero: his crossing of Greenland on foot in 1888 and the legendary Fram expedition of 1893 - 1896.

A childhood with polar promise

A life marked by a relentless pursuit of knowledge, adventure, and the limits of human endurance began in 1861 with Fridtjof's birth in Norway. The young Nansen had statesman blood in his veins through the family trees of both of his parents, and a comfortable early life laid the groundwork for his life work through summers spent hunting and the honing of outdoor pursuits and survival skills while skiing excursions dominated his childhood winters.

Nansen went on to study zoology and, on his professor's suggestion, seized the opportunity to study Arctic zoology firsthand aboard the sealer Viking in 1882. As Viking sailed between Greenland and Spitsbergen in search of seals, the ship became stuck in ice off the shore of Greenland, marking Nansen's first encounter with this almost entirely unknown landmass, and sparking an idea that would later be fully realized - the crossing of the Greenland ice cap.

After returning to Norway, Nansen continued his studies, taking up the post of curator at the Bergen Museum, and published a doctoral thesis in 1887. Throughout these six years, he fermented a vision and forming a plan for his triumphant return to the shores of Greenland.

Photo by API/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Into the unknown: Nansen's Greenland crossing

In 1888 much of Greenland's landscape remained unknown, an unmapped and harsh world of ice and rock. No one had successfully crossed it from coast to coast. Inspired by the expeditions of Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1883) and Robert Peary (1886), Nansen began to plan his expedition in 1887. His vision was to cross from east to west, effectively stranding him and his men on the largely inaccessible east coast. This meant that Nansen and his team would have no option but to push to the west no matter what.

In July 1888, Nansen, accompanied by five men on skis and man hauling their sledges, set out from the sealer Jason, forced to start their expedition some 200km south of their intended launch point, and delayed by over a month spent attempting to reach the shore in small boats amid heavy sea ice.

Leaving Umivik on 15 August, the party almost immediately encountered challenging ascents, fierce weather, and a dangerous world of crevasses, ice cliffs, and brutal open ice caps. With temperatures dropping below -40 degrees at night after reaching the plateau at 2,719 meters (8,921 ft), the men struggled to stay warm. Quite soon, it was clear that their intended destination, Disko Bay, was out of reach if they wished to arrive before the final ship of the season departed, so Nansen rerouted the team to Godthåb (modern-day Nuuk), which they reached after covering around 500 km of unknown land in around two months.

Photo by Print Collector/Getty Images

Celebrated on their arrival, Nansen and his men learned they would not be picked up until the following Spring. Yet, their mood was undimmed - they had achieved their aim of becoming the first to complete a trans-Greenland crossing, recorded data on ice thickness, meteorology, and geography, and established new standards for polar fieldwork.

Their success also marked a turning point in the philosophy of Arctic exploration, demonstrating the benefits of small, mobile teams over large, cumbersome expeditions.

Nansen's Zenith: The Fram expedition to The Pole

Now celebrated in Norway, Nansen set his eyes on an even more ambitious goal - the North Pole. He became convinced by a theory proposed by meteorologist Henrik Mohn regarding transpolar drift that the natural drift of the sea ice could be harnessed to reach the North Pole. In the mid-1880s, wreckage from USS Jeannette, which had been crushed by pack ice off the Siberian Coast, was discovered on the coast of Greenland - the exact opposite side of the Arctic Ocean.

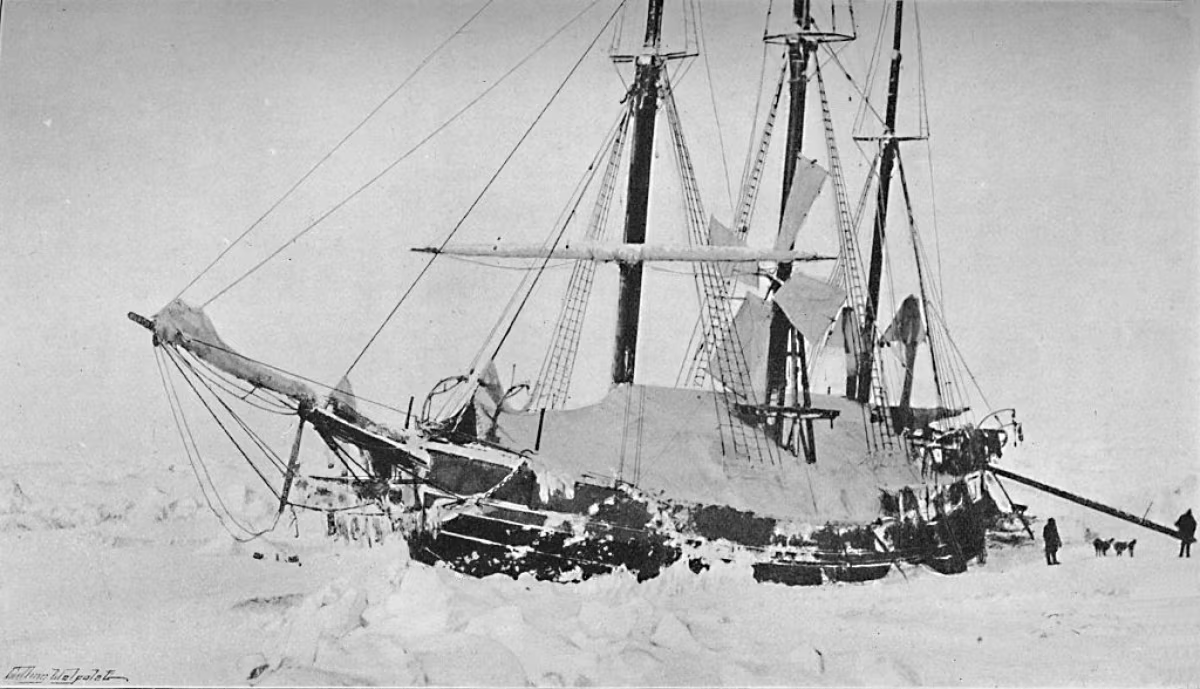

Convinced that ocean currents flowed across the pole from Siberia to Greenland, he commissioned the designing of a ship - the Fram - specifically built to withstand being frozen into and carried along by the pack ice.

Photo by Print Collector/Getty Images

In 1893, Nansen set sail from Norway aboard Fram, accompanied by a party of 12 carefully selected crew, including Hjalmar Johansen. By September, Nansen recorded their position as 78°49′N 132°53′E, the ship's engines were stopped, and their drift in the ice began off the Siberian coast. The Fram moved with the Arctic currents for over a year, often dragged south, and only passed 80°N in March 1894. In November, Nansen announced a change in the plan. It was clear that the drift would not carry them directly over the pole, and instead, he and one companion would set out across the ice on foot, aiming to get as close to the pole as possible.

Making a dash for The Pole

After the ship passed 84°N in March 1895, Nansen and Hjalmar Johansen left the safety of the Fram and set out across the ice with dog sleds and kayaks, aiming to get as close to the pole as possible. After a week, they had covered an average of 17 km (10 mi) per day. However, they began encountering huge ice blocks and increasingly uneven terrain. By 7 April, they had decided to turn back, having recorded a then-record latitude of 86°13′N. Yet, their journey was not over.

On their retreat south, a mistake led to the loss of both chronometers - instruments critical in calculating longitude and leaving them unable to accurately plot their route to Franz Josef Land. Yet, they forged ahead, encountering increasingly warm weather, which began to break up ice, making the going treacherous and ever more difficult. By July, the pair sighted land, reaching the edge of the ice floe by early August.

Unsure of their exact position, the pair recognized that they would need to overwinter, so they constructed a small stone hut to serve as their home for eight months.

Photo by Print Collector/Getty Images

A chance rescue and international acclaim

After a winter spent consuming bear & seal meat, and preparing for the onward journey, Nansen and Johansen set out from their winter quarters in May 1896. On 17 June, while they stopped for repairs after being attacked by walruses, the barking of dogs and the hint of human voices drifted on the air. Upon investigation, Nansen saw a man approach. Upon being asked if he was Nansen, he stuttered a bewildered reply, ''Yes, I am Nansen."

They had encountered the British explorer Fredrick Jackson, who was leading an expedition to Franz Josef Land, entirely by chance. They had survived an arduous journey of over 15 months in extreme conditions, setting a new northern record, and pushing the boundaries of what was possible at the time.

In August 1896, Fram emerged from the pack ice northwest of Spitsbergen, proving Nansen's theory of polar drift correct, despite having not reached the pole. With all hands safe and valuable scientific data having been collected alongside a new northern record established, the expedition was celebrated as a resounding success in terms of scientific data and human achievement.

Photo by Print Collector/Getty Images

An enduring Polar Legacy

Nansen's expeditions redefined what was possible in the polar regions. He introduced innovations in clothing, equipment, and strategy that would be adopted by future explorers, including Roald Amundsen, who credited Nansen as a significant influence. His image was such that he was considered a polar oracle, advising many other polar explorers, including Robert Falcon Scott, on their own preparations and plans.

After retiring from polar travel, Nansen turned his attention to science and diplomacy. He became a well-regarded oceanographer and a renowned humanitarian, earning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922 for his work aiding refugees after World War I through the League of Nations. He had associations with many prestigious organizations, including the Royal Geographical Society. He undertook various research in the Arctic on several further voyages on many differing subjects, leaving a legacy that extends beyond the realms of the polar world.

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

His ship, the Fram, preserved in Oslo's Fram Museum, stands today as a monument to his achievements, along with the many geographical landmarks named in his honor. Fram would go on to be used by Roald Amundsen in his successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911.

In an age where satellites and icebreakers now chart the polar regions, Nansen's story remains a powerful reminder of what can be achieved through vision, resilience, and the unyielding desire to explore the unknown. His 1888 crossing of Greenland and the legendary Fram expedition of 1893–1896 laid the groundwork for a new era of polar exploration and left a legacy that continues to inspire today.

Main image by Hulton Archive/Getty Images