Robert Falcon Scott’s race for the South Pole

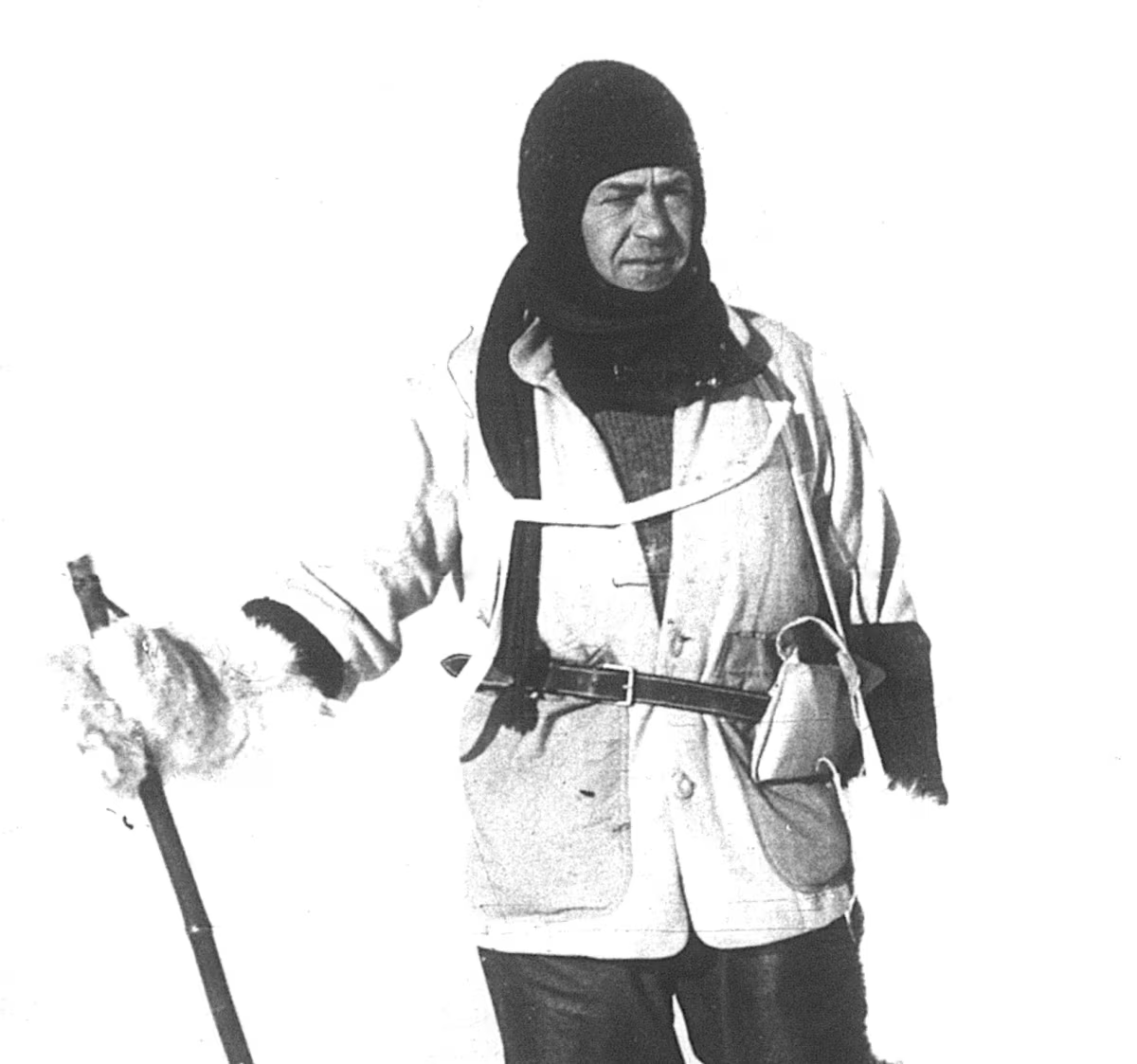

When Captain Robert Falcon Scott embarked on his second and final expedition to Antarctica in 1910, he was already a famous explorer.

Having led the Discovery Expedition (also known as the National Antarctic Expedition of 1901-1904), where he reached a record 82°11’ south, he next set his sights on the South Pole. But he was not alone. Aware of how close Shackleton had come to reaching this goal, Scott quickly set about planning his British Antarctic Expedition (1910-1913) to claim the Geographical South Pole for Britain.

Shackleton’s valiant but unsuccessful South Pole expedition

Not long before Scott’s South Pole expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s British Antarctic Expedition (1907-1909) made a significant number of firsts. In March 1908, his party of five was first to climb the world’s southernmost volcano (Mt. Erebus), and in late 1908 he led a party of four to reach the Geographic South Pole.

But after man-hauling sledges for two and a half months, Shackleton turned back within 97 miles of his goal due to failing supplies and exhaustion. He had ventured farther south than anyone before him, receiving a hero's welcome and knighthood back home. His expedition had discovered over 800km (500 miles) of new mountain ranges and pioneered the way to the Antarctic Plateau.

Scott’s British Antarctic Expedition (1910-1913)

Scott resigned from the Royal Navy in 1909 to concentrate on planning and raising money for his South Pole expedition. The British government pledged £20,000, and the governments of New Zealand and Australia also contributed, along with various business people and private donors. Scott even sold berths in the expedition to raise money, raising a total of £40,000.

In addition to reaching the South Pole, he planned a comprehensive scientific program with Dr. Edward Wilson, his senior scientist. Together they assembled a group of scientists with backgrounds in meteorology, glaciology, geology, and marine biology. They chose for their expedition the vessel Terra Nova, originally built as a whaler and later serving as the relief ship on his Discovery Expedition.

News of Amundsen en route to Antarctica

While in Melbourne on his way to Antarctica, Scott received news that Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen was competing with him for the South Pole, having been beaten to the North Pole by American explorers Robert Peary and Matthew Henson.

Scott was undeterred, continuing preparations as they sailed for New Zealand, and on November 29 Terra Nova sailed south from Lyttelton, New Zealand. On board was a large number of animals and supplies, such as 162 carcasses of mutton, three Wolsely motor tractors, 33 Siberian huskies, 17 Manchurian ponies, and ample medical tools and surveying gear. Also on board was a prefabricated hut designed for harsh winter conditions.

Scott’s hut at Cape Evans

The expedition arrived at Ross Island in January of 1911 to set up base. Thick sea-ice prevented Terra Nova from reaching the old Discovery hut, so on January 4 Scott landed at the Skuary, which he had named in 1902 due to the large number of skuas living there. Scott renamed the area Cape Evans after the expedition's second-in-command, Lieutenant Edward "Teddy" Evans. From Cape Evans, there are views over McMurdo Sound, the Trans-Antarctic Mountains, and the Dellbridge Islands.

After inspecting the site, Scott and his crew began constructing their hut. Nine days later Scott's hut was finished, the largest building constructed in Antarctica during the Heroic Age. According to Scott, it was "the most comfortable dwelling-place imaginable…within the walls of which peace, quiet and comfort remain supreme."

Sixteen officers and scientists lodged in the wardroom, while nine other crewmen (including the seamen) quartered in the messdeck. The wardroom had a large table, which on Sunday’s was covered with a dark blue cloth for meals, along with a piano and gramophone.

Cubicles with bunks were built around the wardroom. Scott's bunk was partially enclosed by a timber partition and contained his bed, chart table, and bookshelves. In the messdeck were nine beds for the men, along with two tables for dining and food preparation. The hut also had a darkroom with workbenches for the scientists.

Over the harsh winter, the men conducted observations, prepared sledge equipment, and exercised their dogs and ponies. They held elaborate dinners on Scott's birthday and at midwinter, serving such meals as seal soup, Yorkshire pudding, and mince pies.

Scott's push for the South Pole

When spring finally came, the journey to the South Pole began. The first team was dispatched on October 24 with two motor sledges, and Scott followed with a larger party of 10 ponies on October 31. The various teams relayed supplies and set up caches, progressively turning back to leave the next party on their own.

On January 4, 1912, the last support party turned back, leaving Captain Scott, Edward Wilson, Lawrence Oates, Edgar Evans, and Henry Bowers to make the final push for the South Pole. The party reached their destination on January 17 to find the small green tent Amundsen had left there some 35 days earlier.

Scott and his crew never survived the return journey, perishing just 11 miles from a supply depot. Scott's last words in his diary read, "We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence, determined still to do our best to the last."