Was it Robert Peary or his largely forgotten partner, Matthew Henson, who first reached the Geographic North Pole?

For over a century, polar historians have generally agreed that American Navy engineer Robert Peary was the first person to reach the Geographic North Pole. But studies made over the last several decades assert that it was actually Peary’s African American associate, Matthew Henson, who got there ahead of him – despite losing eight of his toes to frostbite.

Peary’s much-studied and much-contested 1909 expedition to the North Pole was the last of eight and the only one to achieve its ultimate objective. And though the man’s claim to have made it to the pole first (or at all) was disputed from the start, it was only more recently that polar scholars began sliding Henson into his place.

Some of these scholars, such as British explorer Wally Herbert, science journalist John Noble Wilford, and City Journal editor John Tierney, focused chiefly on the veracity of Peary’s claim to have reached the pole, citing the lack of essential data in his notebook. But some subsequent studies indicate Peary knowingly stole the credit from Henson.

These studies, which include a 2014 book entitled The Adventure Gap by James Mills and a National Geographic article by the same author, put stock in Henson’s account over Peary’s. According to Henson, he overshot the area Peary later identified as the North Pole while on a scouting mission during the final stage of their journey. When he and Peary came back to that area and verified it was their goal, they saw Henson’s footprints already there.

Nonetheless, Peary returned home to take full credit for being the first man to the North Pole. And while he was awarded medals, promotions, and a generous Navy pension, Henson faded into relative obscurity. In fact, he would only receive the recognition he deserved in the final years of his life, more than three decades after their partnership ended.

As outrageous as this outcome is to our modern sensibilities, it was unfortunately commonplace throughout the heyday of polar exploration and discovery. To better understand the historical context of the Peary-Henson expedition, as well as the complicated dynamic between the two men, it helps to look further back.

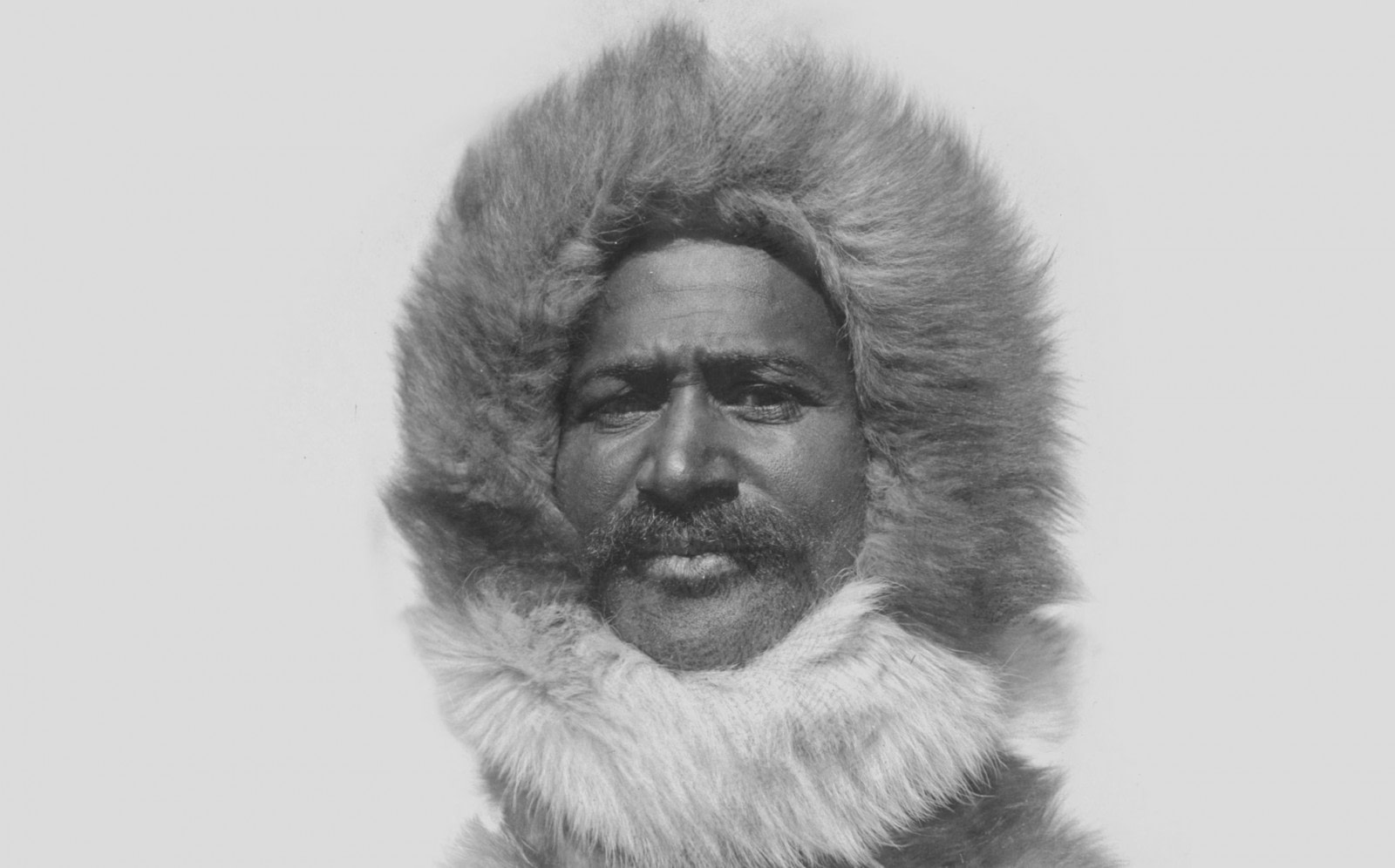

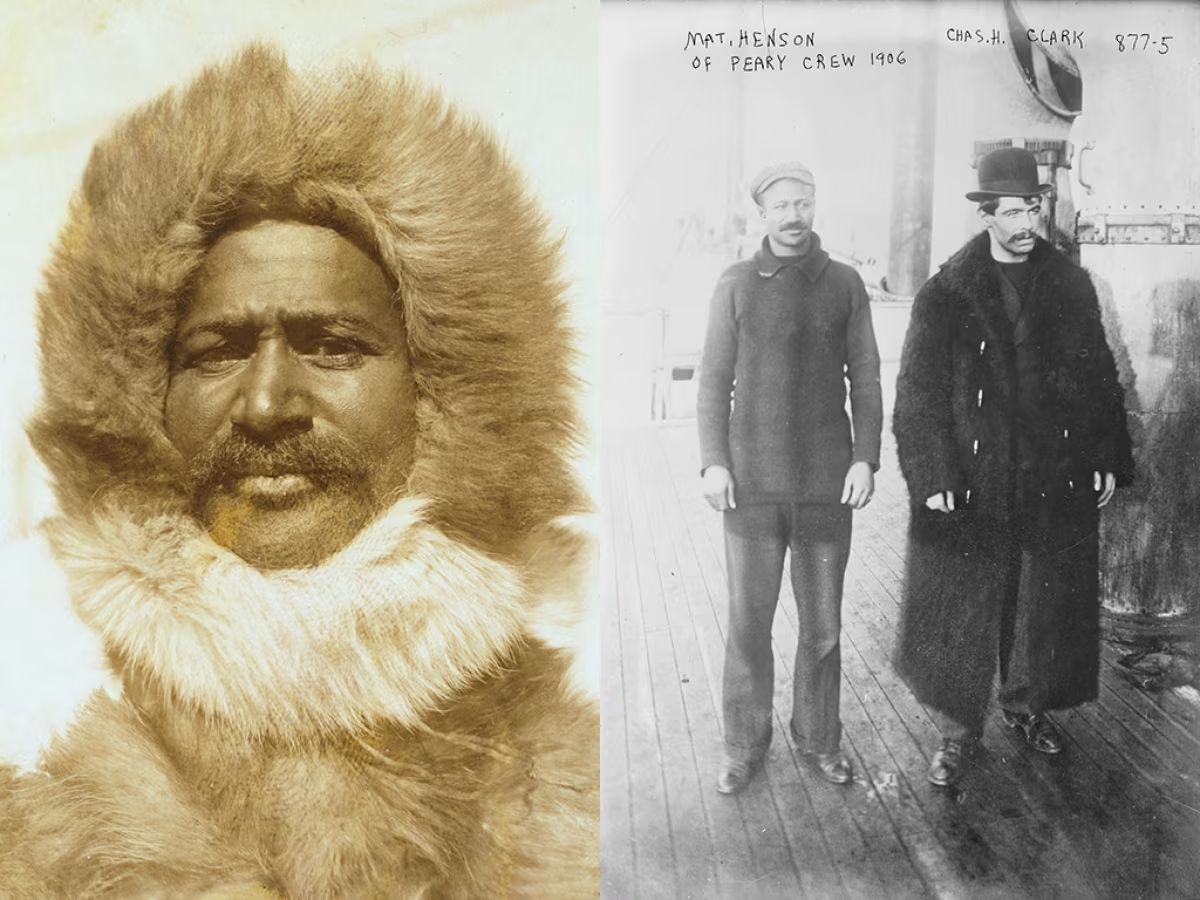

Image by National Archives at College Park

Matthew Alexander Henson was born on August 8, 1866, in Charles county, Maryland, just one year after the end of the Civil War and the enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. He was orphaned as a child and went to sea at the age of twelve, becoming a capable cabin boy aboard the three-masted sailing ship, Katie Hines.

He would remain on the ship for the next six years, sharpening his sailing skills, receiving an education from the captain, and visiting such distant areas as North Africa, the Black Sea, and various regions of Asia. When his captain died in 1887, Henson took a job as a clerk in a fur store in Washington, DC. It was here that he met Robert Edwin Peary.

Impressed by Henson’s nautical knowledge and sense of adventure, Peary immediately hired him as a personal valet on his 1888 Nicaragua expedition, bringing Henson into the Navy Corps of Civil Engineers. Henson’s core duties involved mapping the Nicaraguan jungle with Peary, who was trying to survey the route for a canal that could connect the Pacific Ocean with the Atlantic. But this canal was never built, and after two years of scouring the Central American rainforests, the partnership between Peary and Henson temporarily ended.

The moment Peary got financing for another expedition, however, Henson was his first hire. But the new expedition would take place in a much different area of the world than Nicaragua, venturing into the farthest sweeps of the Arctic with the goal of reaching the Geographic North Pole. Spanning from 1891 to 1909, this multi-stage mission would represent the pinnacle of their careers and remain a matter of contention for years to come.

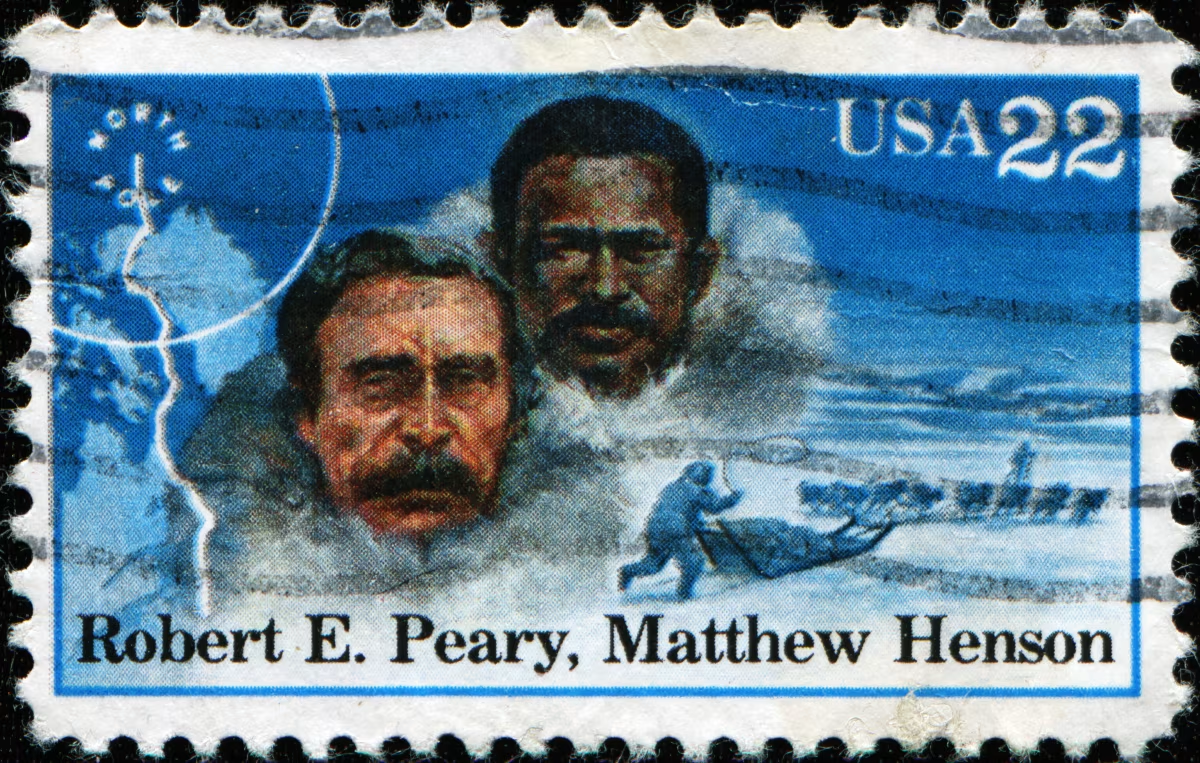

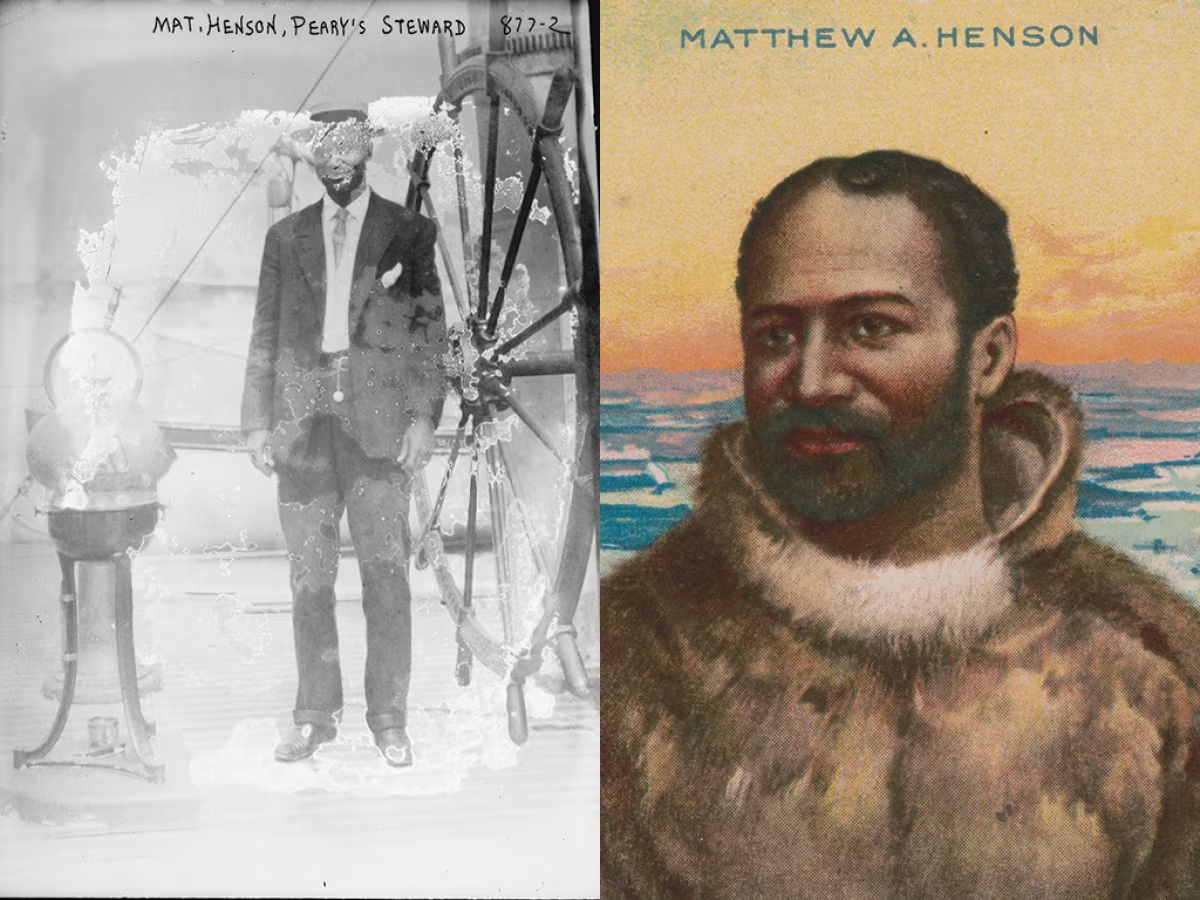

Image by Bain News Service

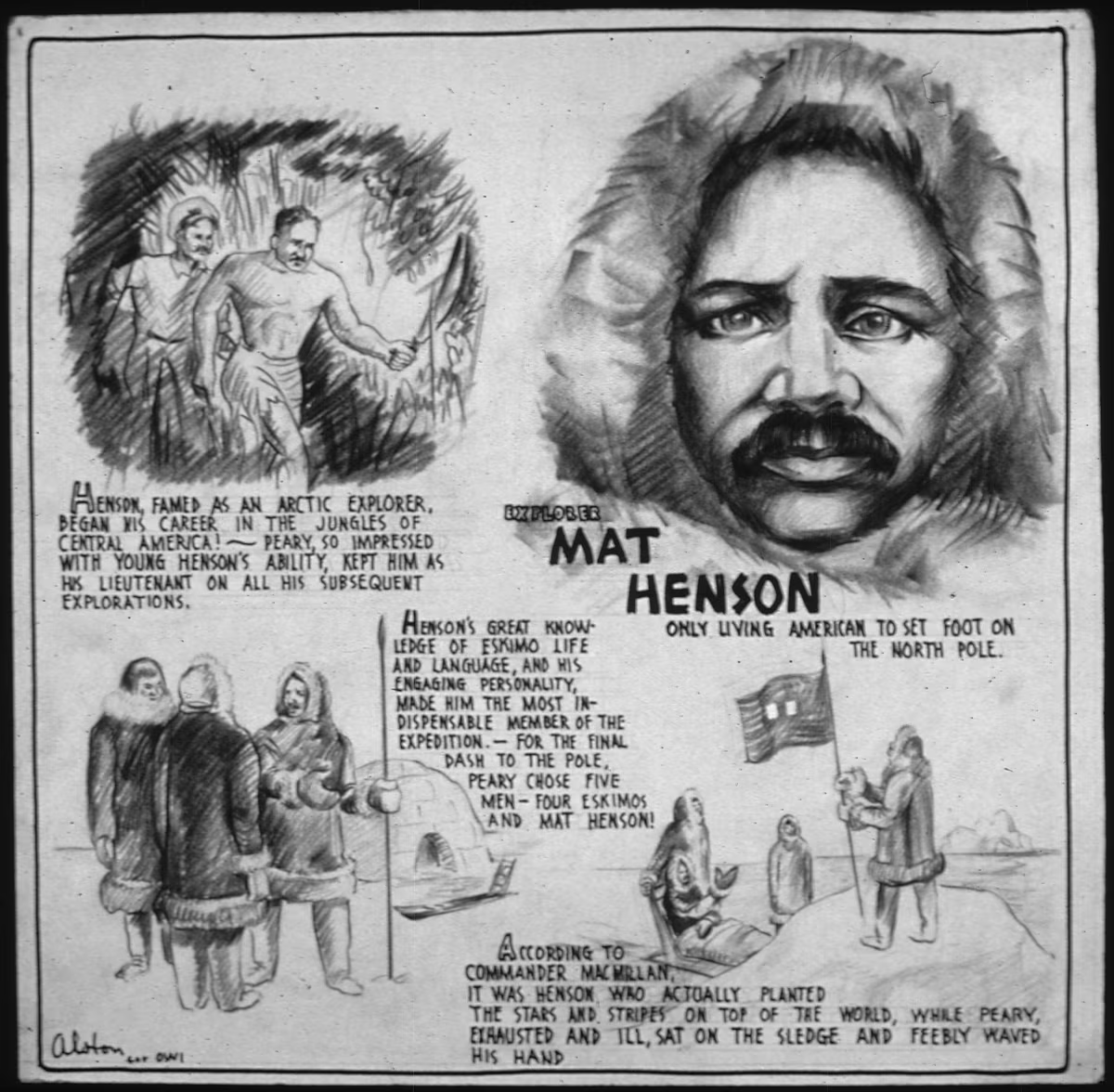

A trend developed over the course of their eight Arctic expeditions that saw Henson leading in the field while Peary lead in public. Unlike Peary, Henson was fluent in the language of their Inuit associates, among whom he was known as “Matthew the Kind One.” Also unlike Peary, Henson was nearly as good as the Inuit at building, maintaining, and driving the company’s sledges, their primary means of travel over the Arctic pack ice.

Henson learned and adopted various Inuit skills in order to manage the harsh Arctic conditions, becoming a skilled dog handler, fisherman, and hunter. Eventually, he came to train even Peary’s most experienced crew members, and even Peary would later submit that a great deal of his expeditions’ overall success was due to Henson.

After seven previous attempts to reach the North Pole, nearly all of which got them a little closer to their goal, the final push came when both men were well into their forties. The strain of the task ahead and the toll their previous expeditions had taken on them compelled Henson and Peary to agree that this attempt would be their last.

Image by Frederick Cook & The Smithsonian

They sailed the Roosevelt out of New York Harbor on July 6, 1908 with a carefully hand-picked team. By September 5, 1908, they had arrived in Cape Sheridan, after which they spent the long, dark Arctic winter storing meat supplies while the wives of their Inuit companions sewed clothing. In February, they moved to their forward base camp at Cape Columbia.

The official trek to the pole began on March 1, 1909, when Henson lead the first team of sledges across the ice. Over the next five weeks, the race was on.

To say the explorers met with brutal conditions is an understatement. Temperatures frequently dropped to 65°F (54°C) below freezing, and the pack ice below their sledges drifted and cracked, creating treacherous patches of open water called leads that threatened to block their way ahead and behind. Most of the Arctic, we must remember, is simply sea water covered with moving ice, and the North Pole lies right in the center of it. Henson and Peary were essentially sledding across miles of black, pitiless an ocean.

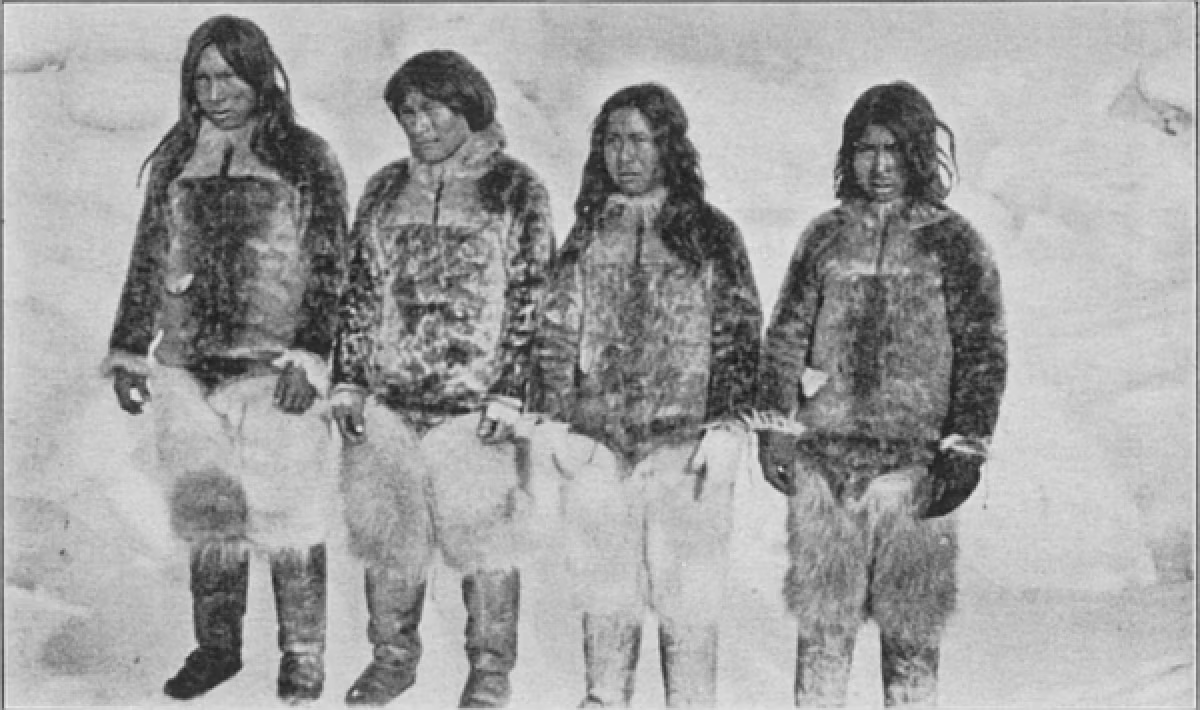

Henson’s account of their final trek is detailed and unambiguous. With Peary and four Inuit associates named Seegloo, Ootah, Ooqueah, and Egingwah, he drove their sledges at a grueling pace in stretches of 12 to 14 hours per day. Afraid that leads might open that would trap them on the ice, they moved quickly, navigating by dead-reckoning and sexton.

On the evening April 5th, after more than 170 miles (275 km) of backbreaking travel, they stopped to build their igloos amid a deep fog. According his summary, Henson was the lead sledge that day and had scouted far ahead of Peary. But as the team lay to sleep, the fog was too thick to reckon their location. They did not know that they – that is, Henson – had already reached the Geographic North Pole, and had in fact gone past it.

The following morning, April 6th, Peary rose early, and without waking his partner as was their usual custom, hurried out of camp with at least one of their Inuit companions, determined to reach the pole first.

When Henson woke up, he was heartbroken. But he soon caught up with Peary, and in a newspaper article later reported, “I was in the lead that had overshot the mark by a couple of miles…and I could see that my footprints were the first at the spot.” That spot was a block of ice 413 nautical miles off the coast of Greenland.

Peary, who had been so tense leading up to that moment that he had barely spoken to Henson, reportedly all but disowned him after their objective was reached. Saddened that twenty-two years of friendship could so quickly evaporate, Henson was even more crushed to return home to find Peary receiving all the credit for their joint effort.

While Peary was heralded as a hero, Henson was relegated to the role of loyal sidekick. Peary received a promotion to rear admiral, a comfortable pension, and numerous recognitions and awards. Henson, on the other hand, was all but forgotten, receiving a minor post as a clerk in the US Customs House in New York City on President Taft’s recommendation and giving occasional small lectures about his experiences.

Image by Bain News Service

Scholars have disputed Peary’s claims to have reached the North Pole for a few core reasons. First, nobody who accompanied him during the final stage of his expedition was trained in navigation, so no one could confirm his claims to have reached the pole. Second, his reports as to the speeds and distances accomplished after his support group doubled back to camp were nearly three times what he had achieved until that point, completely defying belief. Third, Peary’s account of a direct-line trek to the pole is contradicted by Henson’s account of numerous detours around open leads and pressure ridges.

In his book, Ninety Degrees North: The Quest for the North Pole, author Fergus Fleming writes of Peary’s towering egotism, his need to triumph over those around him, and his unwillingness to share the credit of his expedition with a black man – even one who had saved his life on a previous expedition and who had, despite Peary’s infamous arrogance, remained by his side while many of his other associates had abandoned him.

It was not until after Henson’s retirement as a customs clerk, a post he held for 23 years, that his long-overdue recognition arrived. In 1944 he was awarded the Congressional Silver Medal, the same medal Peary had received more than thirty years earlier. And in 1947, Henson published a book about his expeditions entitled A Negro at the North Pole, which includes a forward by Booker T. Washington.

Image by New York World Telegram & The Sun Newspaper

Not long after the publication of this book, the Explorers Club of New York made Henson an honorary member. And in 1954, he was invited to the White House by President Eisenhower to receive a special commendation for his work as an explorer.

Even after his death, Henson’s recognitions continued. In 1996 an oceanographic ship was named the U.S.N.S Henson, and in 2000 the National Geographic Society posthumously awarded him the Hubbard Medal, their most prestigious award. Any guesses who first won that award when it was created in 1906?

Matthew Henson died on March 9th, 1955, in the Bronx. On April 6th, 1988, exactly 79 years after Henson reached the Geographic North Pole, his remains were moved next to Peary’s at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Despite the military honors of the event, it seems fair to wonder how much Henson would agree with this decision.

Left image: dctim1, CC BY-SA 2.0 & right image: Tim1965, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

But whoever technically reached the North Pole first, Henson and Peary were both part of the same expedition. If credit belongs to either of them, it belongs to both of them, and it belongs at least as much to their Inuit companions - none of whom, by the way, are said to have received any formal recognition for their hard work and courage.

Unfortunately, a lot of the historic expeditions ended like this. Both the fierce competitiveness of these endeavors and the ethnic dynamics of the era in which they occurred largely precluded any fair division of credit. Beyond words of praise or helping their dutiful sidekicks secure a modest job, most white men simply could not tolerate sharing any substantial portion of their glory with people of color.

Tragic as that is, we are happy to recognize such overlooked explorers in our own modest way. All those involved in the race to reach the Geographic North Pole overcame enormous obstacles, both external and internal, to achieve their objective. For this and for the inspiration their accomplishments still give to the world of Arctic travel, we feel these brave explorers deserve our remembrance, recognition, and respect to this very day.

Maybe some just a little more than others.

Main image: © Unknown author - This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3g07503